Our Historical Efforts to Reduce the Risks of Smoking

In the 1950s, tobacco product manufacturers began Research and Development (R&D) into the impact of tobacco use, following seminal research by Doll and Hill on lung cancer.[1]

BAT’s R&D facility opened in Southampton, UK in 1956. Initial research focused on trying to understand the issues surrounding smoking and health.

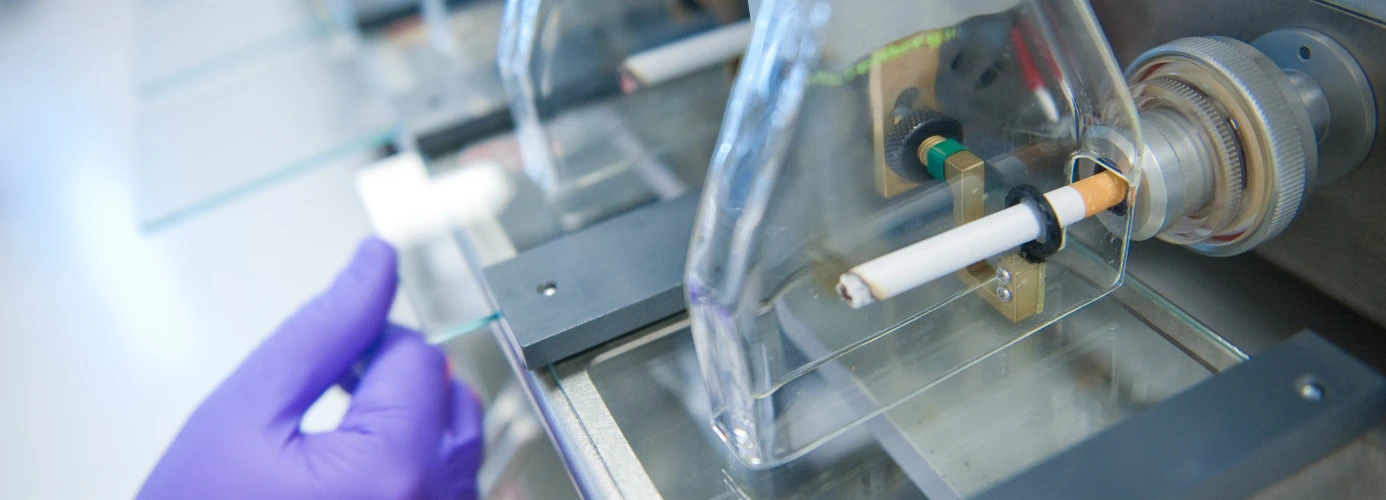

"In the late 2000s we developed a prototype cigarette for scientific assessment."

Dr Chris Proctor

Former BAT Chief Scientific Officer

Sign up for more exclusive the Omni™ content

When tobacco is combusted at around 950°C, it produces smoke comprising more than 7,500 compounds, of which around 150 are known toxicants.[2,3,4]

Over the decades, research expanded into novel technologies to reduce toxicants in cigarette smoke emissions.

These technologies can be split into five areas:

01

Tobacco selection with low levels of toxicants and pre-cursors

02

An enzyme treated novel tobacco with lower levels of toxicants

03

Non-tobacco dilution technologies that could be blended with tobacco

04

Filtration technologies that could reduce vapour phase toxicants

05

Filtration technologies that could remove specific toxicants

Historically, certain cigarettes were developed that used treated tobacco or carbon filters to potentially reduce exposure to the carcinogens found in cigarette smoke.[5,6] Ultimately, due to lack of consumer interest and acceptability, some of these cigarettes were removed from the market.[7]

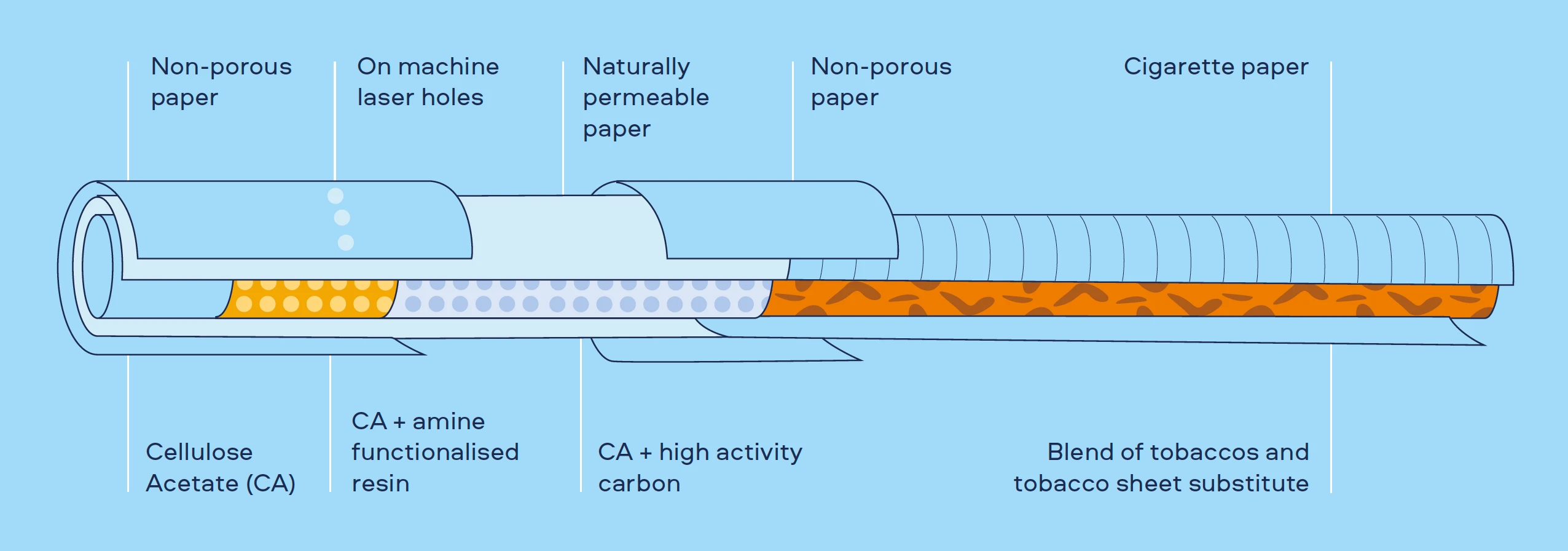

In the late 2000s, we developed a prototype cigarette for scientific assessment using a combination of these technologies – the Reduced Toxicant Prototype (RTP) cigarette. It was assessed to measure and understand the emissions, exposure, and potential risk, relative to smoking a conventional cigarette (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Overview of the design and scientific assessment of the Reduced Toxicant Prototype (RTP) Cigarette

After extensive research, the toxicant levels of emissions from the RTP cigarette and its subsequent toxicological impact were reduced when compared to conventional cigarette smoke.[8,9] However, clinical results showed that adult smokers who used the RTP cigarette had the same levels in Biomarkers of Potential Harm# (BoPHs) as adult smokers of conventional cigarettes.[10]

It was concluded that the RTP cigarette was not a reduced-risk product. We published our data in a series of papers to show that, when tobacco was combusted in a cigarette, the technologies in the RTP cigarette would facilitate lower levels of toxicants, with lower toxicological impact, exposing adult smokers to lower levels of toxicants. However, crucially, these changes did not translate into a likely reduction in risk.

This conclusion, along with our historical research, formed the basis of the re-articulation of our THR strategy in 2013, which pivoted from combustible to non-combustible (smokeless) tobacco and nicotine products, and resulted in the launch of our first Vapour Product in July 2013.

Reduced emissions

Overall changes in RTP toxicant yields compared to a conventional commercial cigarette[8,10]

Favourable Change |

||

| Crotonaldehyde | 90%▼ | Yes |

| NNN | 86%▼ | Yes |

| Acrylonitrile | 95%▼ | Yes |

| NNK | 62%▼ | Yes |

| Acrolein | 94%▼ | Yes |

| 3-ABP | 44%▼ | Yes |

| 1,3-Butadiene | 87%▼ | Yes |

| CO | 19%▼ | Yes |

| 4-ABP | 17%▼ | Yes |

Emissions

Reduced exposure

Overall changes in biomarkers of exposure in RTP adult smokers[10]

Favourable Change |

||

| HMPMA | 75%▼ | Yes |

| Total NNN | 65%▼ | Yes |

| CEMA | 57%▼ | Yes |

| Total NNAL | 39%▼ | Yes |

| HPMA | 34%▼ | Yes |

| 3-ABP | 31%▼ | Yes |

| MHBMA | 31%▼ | Yes |

| CO | 19%▼ | Yes |

| 4-ABP | 17%▼ | Yes |

Biomarkers of Exposure

Reduction in BoPH

Overall changes in biomarkers of potential harm in RTP adult smokers[10]

Favourable Change |

||

| 11-dh-TXB | 19%▼ | Yes |

8-iso-PGF2 Type III |

3%▲ | No |

8-iso-PGF2 Type VI |

6%▼ | Yes |

White Blood Cell Count |

0% | No Change |

sICAM |

60%▲ | No |

| HDL | 8%▼ | Yes |

Biomarkers of Potential Harm

Footnotes

# Biomarkers of Potential Harm are markers of physiological processes in the body such as inflammation, oxidative stress, and DNA damage. (see Clinical: Individual Risk, Pages 190-193)

References

[5] The Wall Street Journal, A Potentially Less Toxic Cigarette To Get a National Push by Vector. 2001. (Accessed: 20 August 2024)

[7] Reuters, Philip quashes Marlboro Ultra Smooth test. 2008. (Accessed: 20 August 2024)